July, 2025

Background and Use of Scenarios within Workforce Planning

By Tanya Hammond, Wendy Morison, Jaye Matheson and Tessa Spinks

Scenario planning is a strategic technique that helps organisations prepare for the future by exploring multiple plausible outcomes. In the context of workforce planning (WFP), a scenario is defined as a “hypothetical, but plausible, story about future events constructed from observed trends and historic data” (CSIRO, 2012). Rather than trying to predict one definitive future, scenario planning allows HR professionals and business leaders to consider a range of alternative futures for the organisation and their workforce. This approach helps organisations address the key question:

“What does our organisation need from its workforce to successfully deliver its business goals now and into the future?”

Scenario planning acknowledges that the future cannot be forecast with absolute certainty and there is no single ‘best way’ that will remain optimal. Instead, it encourages flexibility and forward thinking. As strategy expert Charles Roxburgh noted in regard to scenarios:

“Although it is surprisingly hard to create good ones, they help you ask the right questions and prepare for the unexpected. That is hugely valuable.”

In other words, the value of scenarios lies not in predicting exactly what will happen, but in prompting decision-makers to think broadly and prepare for what might happen.

In workforce planning, we develop scenario narratives to describe the potential future states of the organisation. These narratives are used to inspire decision makers to envision the impacts of key drivers of change on the organisation and its workforce. Scenario planning is a qualitative technique that complements quantitative forecasting by capturing insights beyond what historical data trends alone might suggest. It enables organisations to explore ‘what if’ situations and to identify how different factors could create different workforce and workplace needs. Ultimately, scenario planning in WFP provides a basis for formulating people management strategies that are robust under a variety of future scenarios, thereby helping mitigate future workforce-related risks:

Figure 1: Scenario Planning Horizons

Figure 1: Scenario Planning Horizons illustrates the importance of scenario planning in workforce strategy. It shows how scenarios help in considering plausible organisational futures over a five-year period. The various factors such as employee experience, economic, environmental, labour market and technological drivers are key considerations to ensure the organisation is strategically responsive over the timeframe of the workforce plan.

Why Use Scenarios in Workforce Planning?

Using scenarios in workforce planning helps organisations understand variability in their operating environment and prepares them to meet future workforce needs under different circumstances. Traditional workforce planning often relies on a single predicted future without consideration for what is probable, possible or plausible. (e.g. one set of economic assumptions, one forecast of retirements, etc.). However, this can be risky because the real world might diverge from those assumptions. Scenario planning introduces disciplined imagination into planning:

-

Scenarios acknowledge that multiple outcomes are possible. By considering a few plausible futures, leaders can avoid the trap of falsely assuming one trajectory. This is crucial because workforce-related factors (like skill availability, technology adoption or policy changes) are often uncertain and can change rapidly. Scenarios make WFP more resilient, by recognising uncertainty upfront and preparing for it.

-

Crafting scenarios forces planners to identify and examine the drivers of change in the environment – for example, demographic shifts, new technologies, economic trends or legislative changes. This yields a better understanding of external and internal factors that could impact the workforce. Even if none of the scenarios play out exactly, this insight helps inform strategy. It ensures the workforce plan is aligned with broader strategic context and not developed in a vacuum.

-

Once scenarios are developed, organisations can test their current workforce strategies against the most plausible scenarios to find vulnerabilities or gaps. For instance, a recruitment plan that works in a scenario of high growth might falter if a recession scenario occurs. Through scenario planning, planners can identify which workforce needs are common to all scenarios (those that are “no-regret” actions, to pursue immediately) and which needs diverge (those that might require contingency plans or closer monitoring). This leads to a portfolio of actions and a more flexible, adaptive workforce plan.

-

Scenario planning is typically a collaborative, workshop-based process. It brings together participants from across the organisation (and sometimes external experts) to discuss the future. This engagement can build a shared understanding and commitment to the workforce plan. It encourages creative thinking (what could happen?) alongside analytical thinking. Participants often tell us that scenarios make planning fun and intellectually stimulating, which can increase buy-in for the resulting strategies.

In short, scenario planning adds significant value to workforce planning by broadening the planning horizon beyond the “most likely” future. It helps answer not just where we are headed, but what if things change? – ensuring that the organisation’s workforce strategy is robust, agile, and future-ready.

How do we conduct scenario planning as part of a workforce planning project?

The following outlines a structured approach that we have found effective in our workforce planning projects:

-

Begin in the early stage of your WFP project (often in our Phase 1: Understand) by clarifying what you want to achieve with scenario planning. Identify the focal issue or your ‘problem’ or ‘challenge’ statement – for example, “future IT skill needs in our organisation” or “staffing levels for a new service model”. Ensure leadership supports the effort and understands that scenarios will inform (not replace) strategic decisions.

Gather information on the organisation’s internal and external context. This includes trends and factors in categories such as Political, Economic, Social, Technological, Legal, and Environmental (PESTLE) that could impact the workforce. Summarise these findings in an “Environmental Scan Overview” or similar digestible format. The environmental scan results are key inputs to the scenario process, providing an evidence base for imagining future changes. (See Useful Links for our article on environmental scanning - Why Environmental Scanning is a Key Input to Workforce Planning.)

Scenario planning is best done through a collaborative workshop. Invite a range of stakeholders who have deep knowledge of the organisation and its environment. This should include senior executives (for strategic insight and buy-in) as well as individuals known for creative thinking who can challenge the status quo. If possible, include a few external perspectives (e.g., industry experts or partners) to avoid groupthink. Before the workshop, distribute the environmental scan summary to participants and ask them to review it and note potential factors in each category that could significantly affect the organisation’s future. This pre-work ensures everyone arrives informed and ready to discuss future drivers of change.

-

At the start of the workshop, discuss the broad range of factors identified through the environmental scan. Through facilitated dialogue, narrow down to the key driving forces that are most likely to shape the organisation and subsequently its future workforce. Typically, these drivers are chosen based on two dimensions: impact (how much the factor could affect the organisation and workforce) and uncertainty (how unpredictable or variable that factor is). Aim to prioritise a handful (usually 2 to 5) of the most critical and uncertain drivers of change. For example, in a government agency context, key drivers might be things like “degree of automation of services”, “labour market supply of critical capabilities”, or “changes in government policy/mandate”.

For each chosen key driver, brainstorm what the extremes of outcomes might look like. A common technique is to define continuums or axes from “least extreme” to “most extreme” outcome for each driver. For instance, a driver “technology adoption in the workplace” might range from minimal adoption to full automation of routine tasks. Another driver “budget availability” might range from constrained funding to significant funding growth. Once you have these continuums, consider pairing or grouping drivers to form the basis of scenario logics. A popular approach is to take the two most impactful/uncertain drivers and cross them, creating a 2x2 matrix with four distinct scenario “worlds”. However, you can also develop scenarios without a formal matrix by logically combining driving forces in different ways. At this stage, the goal is to sketch a few distinct scenario outlines. These represent the broad concepts of each future world and often include nicknames or titles for easy reference.

-

Next, refine the scenario outlines to ensure they are plausible, internally consistent, and relevant. Use the knowledge and judgment of the group to eliminate implausible elements. This is where the futures cone concept comes into play (see Figure 2: The Futures Cone). The futures cone reminds us to avoid futures that are merely possible (anything that could happen, no matter how far-fetched) and instead concentrate on futures that are plausible (could happen given what we know, even if they are not the expected baseline). In practice, this means sanity-checking the scenarios against the change drivers and the group’s expertise. Ask, “Could this scenario really occur and is there some evidence or logical rationale behind it?” Remove or adjust elements that rely on magic or highly unlikely leaps. The scenario narratives should stretch thinking beyond the “probable” (business-as-usual), but they should remain credible and supported by trends or data. Typically, you will settle on 2 to 3 scenarios that represent a range of plausible futures. Having too many scenarios can be overwhelming, or result in limited variability between scenarios, while too few might not capture enough diversity of futures.

-

Now, develop each selected scenario into a narrative story. Give each scenario a descriptive name (e.g., “Digital Transformation Boom” or “Resource-Constrained Adaptation”) to capture its essence. Describe the scenario in terms of the operating environment and how the organisation functions in that future. Importantly, include the workforce implications in the narrative: What is the state of the workforce in this future? What capabilities are in demand or obsolete? How is the organisation staffing and structuring itself? What is employee morale or the employer brand like? The narrative should cover a future time horizon relevant to your planning (often 3-5 years, or sometimes 10+ years for long-term planning). Include quantitative details if possible, to add realism (e.g., “in this scenario, demand for data analysts grows 50%” or “25% of the current workforce retires by 2030” – these can be based on trend data or reasonable extrapolation). Ensure each scenario is internally consistent – the pieces of the story should logically support each other and note down the assumptions you have made in developing the scenario.

-

After drafting the narratives, circulate them with key stakeholders (including those who participated in development and any other decision-makers) for feedback. We also work with the decision-makers to agree on the most plausible scenario for the workforce planning project. There was a time when we utilised two to three scenarios for forecasting and developing the workforce plan, however, we found that the focusing on the underlying assumptions and common themes – if a certain capability (e.g. digital literacy) is needed in all scenarios, that’s a priority to invest in immediately - and agreeing the most plausible scenario to be the most beneficial approach.

We recommend maintaining a ‘watching brief’ on the other scenarios and ensure these are considered as change drivers change and/or when you are iterating your workforce plan. This step helps gain buy-in and ensures the most plausible scenario resonates with leadership perspectives. Stakeholder input might lead to some revisions for clarity or plausibility. Once validated, finalise the scenario narrative and have it approved or at least acknowledged by the project sponsor or leadership. At this point, the organisation has an agreed-upon plausible future scenario to use in its workforce planning.

Finally, use the scenario to inform your workforce plan. Analyse the scenario to determine workforce demand and supply gaps in that future.

Going forward, monitor real-world developments to see which scenario the world seems to be tracking, and be ready to pivot strategies accordingly. Scenario planning is not a one-time exercise; it should be revisited periodically. As new data emerges or as time moves on, the scenario can be updated or replaced to continuously guide strategic workforce decisions.

By following these steps, the scenario planning process becomes systematic and actionable. It ensures that scenario development is not just a theoretical exercise but a practical component of strategic workforce planning, directly feeding into workforce strategies and actions.

Why we focus on the “Plausible Futures”: The “Futures Cone” Concept?

Figure 2: Futures Cone

Not all imagined futures are equally useful for planning – hence the need to focus on plausible scenarios. The Futures Cone is a model that defines different “zones” of the future relative to now, based on levels of certainty and evidence. As time moves forward from the present moment, our certainty about the future diminishes, expanding the cone of possibilities. In workforce planning scenario development, understanding these distinctions helps maintain a balance between creativity and credibility:

Probable Future:

The probable future represents what is most likely to happen if current trends continue uninterrupted. It is essentially an evidence-based forecast – the future we’d expect by extending known historical data and assuming no big surprises. In some situations, an organisation’s probable future can be determined with reasonable confidence (for example, if an industry is very stable or change is slow). In such cases, a single forward projection may suffice for planning. However, in many workforce planning cases, especially strategic ones, data limitations make precise forecasting difficult. There often isn’t enough reliable historical data on workforce variables, or the future conditions might differ qualitatively from the past (think of how remote work adoption in 2020 broke away from past trends). Therefore, relying only on the probable future might give a false sense of certainty. If you do make a single forecast, it should be clearly labelled as probable, not certain.

Plausible Future:

The plausible futures are where scenario planning efforts are best focused. Plausible futures are those that could happen, given what we know today. They may not be the expected outcome, but they have a logical narrative and some backing from trends or experts. This space lies between the predictable probable and the speculative possible. In workforce planning, plausible scenarios combine evidence with imagination. For example, you might envision a scenario where a new technology significantly changes how work is done – there’s evidence the tech is emerging, though it’s not guaranteed to advance that quickly; imagining its impact fills in the gaps. Plausible scenarios should be challenging yet believable, stretching the organisation’s thinking without breaking it. Working in this space yields a set of scenarios (usually 2-4) that are distinct, internally consistent and supported by data points or logical assumptions. This balance ensures each scenario demands a unique response from the organisation, thus testing the robustness of workforce strategies, while still being taken seriously by stakeholders.

Possible Future:

The possible futures encompass everything that could conceivably happen, no matter how outlandish. This is a realm of unlimited imagination – from extreme events to science fiction scenarios. While it’s important to acknowledge that wildcards (low-probability, high-impact events) can occur, planning directly for the entire space of possible futures is not practical. Scenarios that drift into the purely possible space often lack credibility and utility. Without some evidence or logical linkage, you can end up with scenarios that stakeholders dismiss as unrealistic. Moreover, working with too many wildly different scenarios can overwhelm the planning process and lead to analysis paralysis. For workforce planning, we avoid the extremes of the possible realm; for example, a scenario where “suddenly 90% of jobs are done by robots next year” would be too implausible (not grounded in any current trend) to be useful. In summary, the possible future space is theoretically limitless, but strategic planning focuses on a narrower band that’s actionable.

In our approach, after identifying key drivers, we refine the scenario narratives to stay within the plausible zone. The futures cone serves as a mental check: Are we too close to the “probable” (just minor variations of today)? If so, we should be more imaginative so we aren’t blindsided by change. Or are we drifting into “possible” but not plausible (science fiction territory)? If so, we need to pull back to realism. By focusing on the plausible middle ground, the resulting scenarios strike a practical balance. They provide enough diversity to explore different strategic responses, yet enough credibility that leaders will genuinely consider them when making decisions.

To summarise, the probable future is what we think will happen, the possible futures include everything that could happen, and the plausible futures are what might actually happen and are worth preparing for. Effective scenario planning for workforce planning lives in that plausible space – it’s where imagination is guided by insight. Staying in this space ensures the scenarios remain useful tools rather than just storytelling exercises, and it maximises their value in informing workforce planning.

Following are worked examples of what we typically develop:

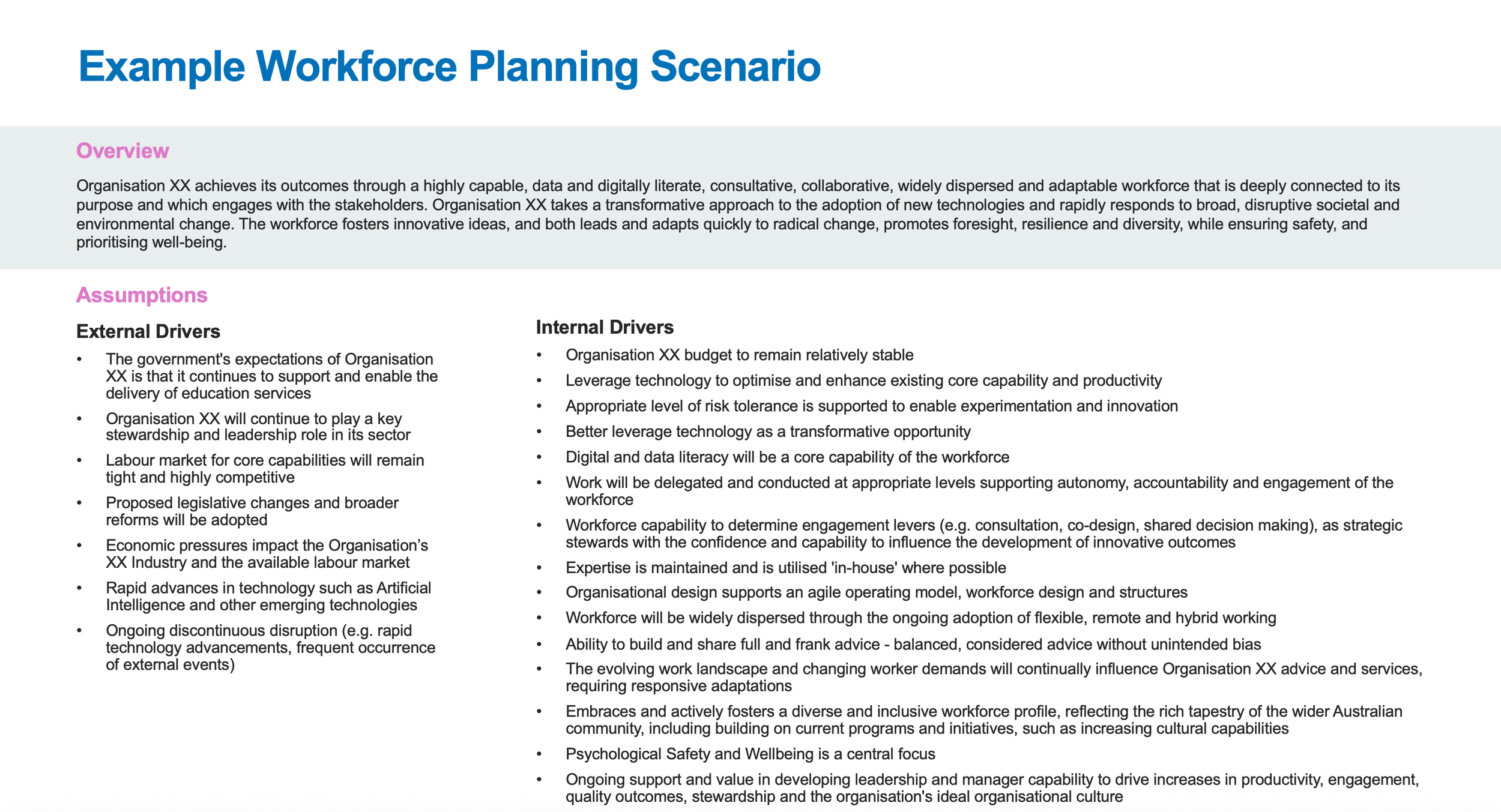

We utilise the most plausible scenarios to prepare a description of the overall scenario which we circulate with key stakeholders to seek their input and signoff. An example of a scenario we have utilised in workforce planning is as follows:

By focussing on the most ‘plausible’ scenario, organisations can better understand the variability within their environment and gain value from articulating the workforce required. A plausible scenario, with a reasonable amount of detail (e.g. percentages, timeframes etc.), enables organisations to be able to be responsive to anticipated changes in their environment, to be agile, and to plan flexibly to ensure they have the required workforce when it is needed.

A further example scenario that a public sector organisation might develop as part of its workforce planning. This scenario is entirely plausible based on current trends:

Scenario 2028 – “Digital Transformation Boom”:

Over the next five years, rapid advancements in technology and a strong political mandate for digital government services transform how the department operates. By 2028, automation and AI have been integrated into 40% of business processes, eliminating routine administrative tasks. The organisation’s services are now delivered predominantly online and citizens expect 24/7 digital access. This shift has two major workforce implications: first, a surge in demand for IT skills (developers, data analysts, cybersecurity experts) leading to intense competition for talent in these areas; second, many traditional roles have evolved, with employees needing to interpret AI outputs and focus on complex, human-centric work. The workforce is leaner but more specialised – total headcount is 10% lower than in 2023, largely due to attrition and automation, but the number of data specialists has tripled. The organisation has retrained a quarter of its staff in new digital capabilities yet still faces a skills gap in emerging technologies (e.g. AI ethics advisors, machine learning engineers). Employee demographics have also shifted: flexible work and a tech-savvy image helped attract younger talent, so the workforce now spans a broader age range with an influx of early-career professionals. However, the pace of change has led to stress and burnout in some teams, prompting the HR team to bolster wellness and resilience programs. In this scenario, the key risk is failing to keep up with tech innovation – the organisation continually partners with private tech firms and upskills its people to avoid obsolescence. It has also revamped its recruitment and onboarding to compete with the private sector, including offering remote work options and mid-career training fellowships to draw necessary talent.

Workforce Planning Implications (for “Digital Transformation Boom”):

In this scenario, the organisation would need to aggressively invest in upskilling programs to transition existing staff into new roles (e.g. training program administrators to become data analysts). Recruitment strategy would focus on attracting high-tech talent, possibly by revising compensation structures or offering unique value propositions (such as meaningful public service projects with cutting-edge tech). Succession planning becomes critical in IT and data roles as those are now mission critical. The organisation might create new job classifications (e.g. Automation Coordinator, AI Ethics Officer) to formalise roles that have emerged. Conversely, some traditional roles might be phased out or combined. The HR team would also need to manage morale and change fatigue by working closely with leadership to pace the implementation of technology and to support employee well-being. Finally, HR policies around remote work and continuous learning would be key enablers in this future – allowing the organisation to tap into a geographically dispersed talent pool and keep employees’ skills current.

The scenario above is one of the “alternative futures” an organisation might prepare for. Another contrasting scenario (not detailed here) could envision a slower pace of technological change coupled with budget cuts, resulting in a very different set of workforce challenges. By comparing Scenario A (high-tech growth) and Scenario B (stagnation and austerity), the organisation can see a spectrum of challenges and strategise accordingly. The takeaway is that each scenario will highlight different workforce needs and strategies, and by considering them now, the organisation can create plans to address each possibility or a blend of them.

Using Scenarios to Inform Workforce Planning

Developing scenarios is only half of the equation – the real payoff comes from using those scenarios to shape and test your workforce plan. Here are some best practices on how to apply scenario insights:

-

Take your current workforce strategy or plan (or proposed initiatives) and evaluate how they would hold up under each scenario. For example, if your plan is to hire 30 new graduates in a certain field, consider: in a scenario where technology reduces need for that role, what then? In a scenario where that talent becomes highly sought-after, can you still achieve it? Identify which strategies are robust across all scenarios and which ones might fail or need alteration in certain futures. This exercise helps pinpoint strategy vulnerabilities. Organisations can use scenarios to assess their workforce strategies for any vulnerabilities. If a strategy only works in one scenario, you may want to adjust it to be more flexible or develop a contingency for the scenario where it doesn’t work.

-

Look across your scenarios for common themes. If, say, leadership development is critical in every scenario (perhaps because every future involves retirements of senior staff), then that’s a ‘‘no-regrets’’ investment to start now. Conversely, note where scenarios diverge. For example, one scenario might require rapid hiring of data scientists while another requires retraining of existing staff in customer service. For those divergent needs, consider creating contingency plans or trigger points. You might not invest fully in them now, but you’ll monitor indicators.

-

Incorporate the most plausible scenario narrative and analysis into your workforce planning documentation. This might be an appendix or a section titled “Scenario Analysis”. Summarise the scenario and the implications for the workforce, and state how the strategic workforce plan addresses them. This not only makes the plan more robust but also demonstrates to stakeholders that a thorough, future-oriented analysis was performed. It can increase confidence in the plan. Moreover, make scenario thinking a part of regular planning updates: for example, each year when you update the workforce plan, revisit whether any scenario is becoming more likely or if new scenarios should be considered due to emerging trends.

-

Once scenarios are defined, identify early indicators that might signal which scenario (or which direction of change) is happening. These could be metrics or events, like turnover rates, technological breakthroughs, policy changes, economic indicators, etc. Assign responsibility to someone (or a team) to monitor these signals periodically. If you start seeing clear signs that align with one scenario, you can then ramp up the corresponding workforce strategies. This makes your workforce plan dynamic – not a static document, but one that can evolve as the environment does. Scenario planning thus feeds into an ongoing foresight practice for HR.

-

Use scenarios as communication tools. They can be very effective in explaining to executives why certain HR strategies are needed. For example, rather than saying “We need to invest in a data science academy”, you can present Scenario “Digital Transformation Boom” and illustrate how without that academy, the organisation in that future would fail its mission for lack of skills. This storytelling approach can make the case for proactive investments or policy changes much more compelling than just using stats or abstract arguments. It drives home the message that “We have thought about this deeply and here’s what could happen…”.

By actively using the scenarios in these ways, the organisation moves from planning to preparedness. The workforce plan becomes more than a set of static predictions – it becomes a living strategy with built-in agility. This ensures that as the future unfolds (whether or not it’s the one you expected), the organisation is not caught off guard. Instead, you have already visualised the potential challenges and have response strategies ready for implementation.

Best Practices and Considerations for Effective Scenario Planning

When developing and applying scenarios in workforce planning, keep in mind the following tips and considerations to maximise effectiveness:

-

Ensure that senior leaders understand the purpose and value of scenario planning. When leadership is on board, they are more likely to seriously consider the scenario outcomes and support the actions that come from the exercise. Brief executives beforehand, perhaps sharing the key question and rationale (e.g. the Roxburgh quote) to set the tone that this is a strategic, valuable exercise.

-

· Encourage workshop participants to be imaginative when brainstorming scenarios but always bring the discussion back to evidence and plausibility when refining scenarios. It’s a dance between thinking outside the box and staying grounded. Use data from the environmental scan to support scenario elements and use expert judgment for areas where data is lacking. This balance will keep scenarios from becoming too conservative or too wild.

-

· Scenario sessions can generate a lot of ideas. Use structured techniques: PESTLE categories for drivers, voting or ranking to prioritise drivers, templates for scenario writing, etc. Assign a facilitator to keep the process on track. Document assumptions clearly for each scenario (e.g. “In Scenario X, assume 2% annual economic growth and a 15% improvement in automation efficiency”). This will help later when communicating or updating scenarios, particularly the agreed ‘most plausible’ scenario you are utilising in your workforce planning.

-

People may have biases like overly focusing on optimistic outcomes or anchoring on recent experiences. To counter this, explicitly ask the group to consider opposite outcomes (for instance, if everyone assumes a driver will trend upward, explore what happens if it trends downward). Sometimes using scenario archetypes (e.g., best case, worst case, wildcard) can force consideration of a broad range. Also, ensure a mix of personalities in the workshop – include both optimists and pessimists, divergent thinkers and convergent thinkers. This diversity can balance biases.

-

When imagining future workforce scenarios, think about all segments of the workforce. For example, if a scenario involves heavy remote work and gig hiring, how might that impact inclusion or employee engagement for different groups? If a scenario involves an aging workforce or a youth influx, what diversity considerations arise? Ensuring your scenarios consider these aspects will lead to more holistic strategies that support all employees in the future.

-

A full scenario planning exercise does take effort – typically a few weeks of preparation and a dedicated workshop (or series of workshops). If resources are limited, you can scale the exercise. For example, do an initial mini-scenario session internally to outline 2 scenarios, and then workshop those further with a broader group. Some analysis is better than none. Over time, as the organisation sees the value, you can invest more in the process.

-

Don’t shelve the scenarios after the planning exercise. Use them in ongoing discussions. For instance, when a new strategic issue arises, relate it to the scenarios: “Does this development push us toward any of our scenarios, or do we need a new one?” Keeping scenario thinking alive in the organisational culture helps make long-term thinking and adaptability part of regular management practice.

-

Write up the scenario narrative and implications in an engaging format. Visuals can help – for example, create a one-pager for your most plausible scenario with a synopsis and bullet points of workforce implications. Share these with the wider organisation if appropriate, to foster broader awareness of possible futures. This can spark productive conversations beyond the planning team, such as with line managers or other departments, about how to prepare for the future.

-

Ensure that scenarios comply with any legal or ethical standards in planning. For example, don’t create a scenario that assumes discriminatory practices (even hypothetically) or one that causes panic. Scenarios should be challenging but not irresponsible. Also, be careful with proprietary data in scenarios if sharing externally – keep them generic enough to not reveal sensitive information.

By following these best practices, scenario planning will be more effective and credible. It transforms from an abstract exercise into a powerful tool that drives strategic decision-making in workforce planning.

Conclusion

In practice, the scenarios developed should continuously inform and challenge your workforce plans. They should be revisited and revised as new information becomes available – scenario planning is not a one-off task but an ongoing mindset. With leadership support and integration into the planning cycle, scenario thinking can become part of the organisational DNA.

In summary, using scenarios within workforce planning enables more robust, flexible, and future-proof HR strategies. It helps the organisation not only to survive in different future states, but to thrive by being proactive and prepared. As the saying goes, “The best way to predict the future is to prepare for it”. Scenario planning offers a structured approach to preparing for multiple futures. Whether the future brings a digital boom, a demographic shift, or an unforeseen crisis, the organisation’s workforce will be equipped to deliver on its mission.

Scenario planning is a cornerstone of strategic workforce planning in an unpredictable world. By initially developing multiple plausible futures, organisations equip themselves to navigate change with agility. The process of scenario development – from scanning the environment, to crafting narratives, to analysing implications – deepens understanding of the forces shaping the workforce. It pushes leaders to consider “What would we do if…?” and to devise strategies that are resilient under various outcomes.

For any organisation, embracing scenario planning means acknowledging that the only constant is change. The workforce you have today is not the workforce you will need tomorrow and the conditions around you can shift rapidly. Scenarios, as detailed in this paper, act as rehearsals for the future. They won’t predict exactly what happens, but they will help you prepare for whatever happens.

Useful links / articles.

Chermack, Thomas J. (2011). Scenario Planning in Organizations: How to Create, Use, and Assess Scenarios. Berrett-Koehler Publishers – A comprehensive book on scenario planning techniques and how organisations can benefit from them. Excerpt link.

Tailored HR Solutions (2025). Why Environmental Scanning is a Key Input to Workforce Planning. (Online article) – Explains the importance of environmental scanning as a foundation for scenario planning and strategic workforce planning.

Roxburgh, Charles (2009). “The Use and Abuse of Scenarios.” McKinsey Quarterly. – An article discussing how business leaders can effectively use scenario planning.

U.S. Office of Personnel Management (2016). Scenario-Based Workforce Planning. – A guide outlining a step-by-step approach to incorporating scenarios in government workforce planning (includes examples and templates for scenario exercises).